What sorts of problems come from forgetting the animistic point of view?

Let’s take a clear example: modern civil engineering and landslide disasters.

Feels like landslides are getting worse every year.

Is extreme weather the cause?

I don’t think that’s the only reason.

In fact, extreme weather is closely tied to what I’m about to explain.

Let me detour via Ingold again.

He uses a phrasing that turns nouns into intransitive verbs—like saying the wind is “winding,” the earth is “earthing,” and so on.

The wind is… “winding”?

Right. I think it points to how activities weave a meshwork.

When we say the wind is “winding,” imagine the wind’s activity as a line within the meshwork.

Within the planet’s cycles, each activity plays a role—you could say it’s the wind fulfilling the role of wind.

By the way, in architecture lately I often hear “Restoration of the Earth” and “Subsurface Environment” (*1). Have you come across them?

Hmm, can’t say I have.

Both draw on landscape techniques and traditional know-how to restore the native cycles of water, air, and living things above ground, in the sky, and in the soil.

I’ve watched related films and joined workshops; with just small interventions in soil and trees I saw nature—previously feeling suffocated—regain circulation and breathe again.

I wondered how that works, and reading Ingold helped it click.

Where wind couldn’t “wind” and soil couldn’t “soil,” we removed what blocked them, letting wind and soil recover their native roles—like restarting stalled lines of activity and returning them to the mesh.

And it doesn’t end as an isolated event: once those intertwined lines re-engage, the whole begins to move—the world as meshwork starts to change.

Wow. If it’s that effective, you’d think it would spread more.

I think so too.

But these ideas and practices are hard to imagine from a Cartesian worldview, so like animism they’re not easy to grasp. (Frankly, I suspect what I’m saying now won’t land with many people either…)

It’s less an objective way to know the world than a way to live within it, which you only really feel by doing.

And even when it works, unlike big, sweeping civil-engineering fixes, this approach tweaks the activities themselves little by little, so it takes time to feel the effects.

A meshwork worldview also resists slicing time into instants—it sees problems across continuing time.

So how does that connect to modern civil engineering and landslides?

Modern civil engineering is essentially Cartesian.

It selects a few subdivided elements, plans from those, and applies the same fix everywhere—overlooking the many activities in the meshwork.

Soil hosts countless organisms; water and air circulate; together they uphold natural order—yet we force concrete structures into that system.

That may work for a while, but once you cut off the flows of water and air, the ground degrades and plants can’t hold the terrain.

Then air and water, with nowhere to go, force their way out, undermining the ground and causing large landslides.

You could say nature is trying to restore its native cycles and activities.

Not that nature “has intent,” but it has a strong tendency to recover circulation when it stalls.

Yet after disaster, we pour even more concrete, again stopping nature’s activity—a cat-and-mouse cycle that can seed more disasters.

Got it—that gives me a picture.

So our current approach just doesn’t see nature’s activities.

Exactly.

Different worldviews trigger problems like this everywhere.

How we grasp the world isn’t armchair theory—it’s more concrete and crucial than we think.

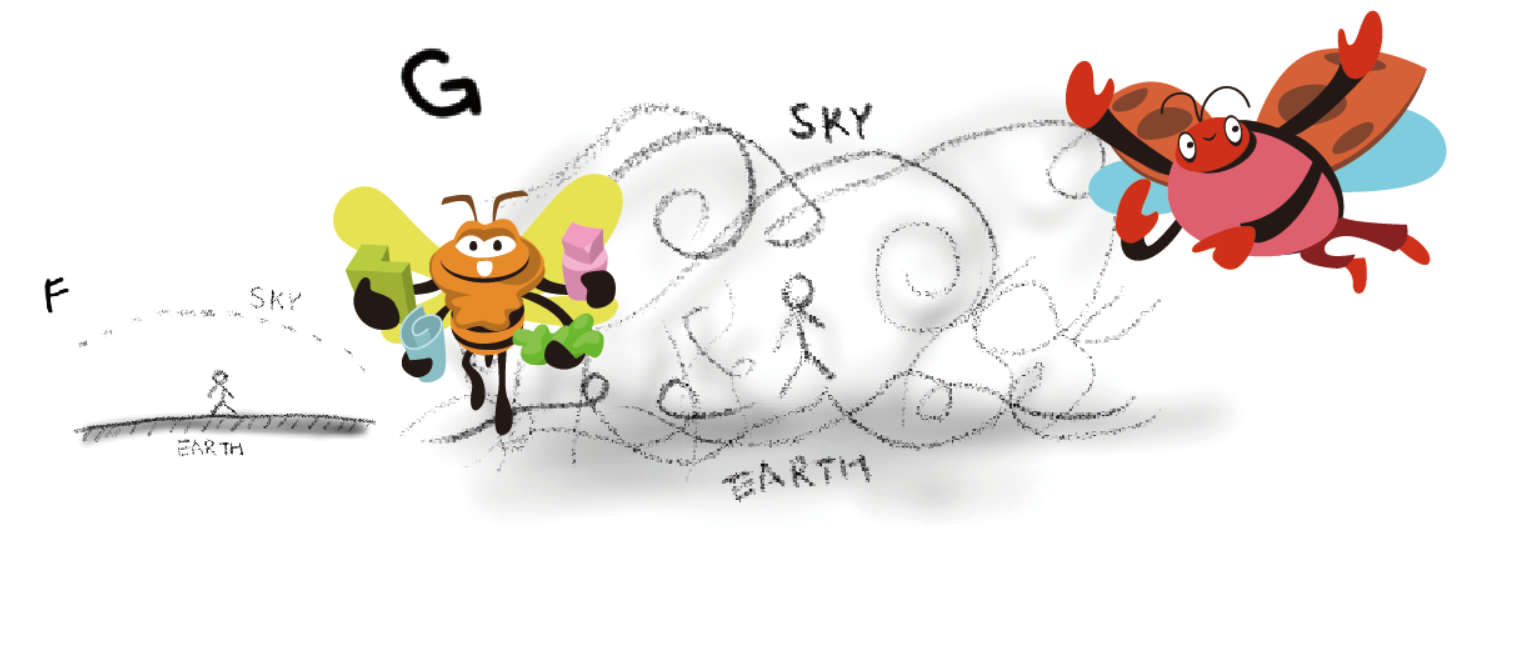

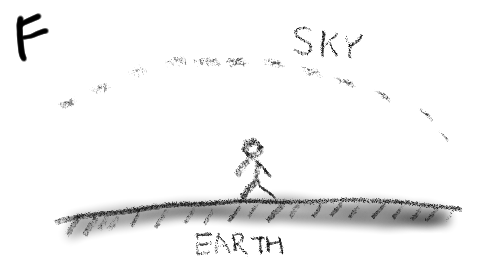

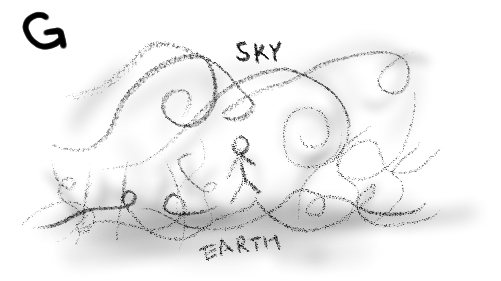

Now, here are two sketches of earth and sky: which one reads as meshwork to you?

This is a long one today!

I’m going with G.

…Bear with me—almost done.

Yes, G is the meshwork-like image.

So, many people tend to perceive land and sky as nouns, like in figure F. That’s the Cartesian worldview—understanding the world in terms of fixed components. In this sense, land is just a lump, and the sky is nothing more than an empty covering.

But here, Ingold suggests: “What if, instead of land-ing the sea, we try sea-ing the land?”

“Sea the land”?

Exactly. From the land, when we look at the sea, we can imagine water circulating, with countless creatures moving within it—in other words, we can imagine the sea as sea-ing.

But land, we often just treat as a static mass. So instead, let’s imagine the land the same way: as full of flows of water and air, teeming with life and activity—a meshwork in itself.

And the same goes for the sky, where winds flow, birds fly, and sounds resonate.

When we start to imagine the world as full of activity rather than fixed objects, the once-static world suddenly comes alive.

Oh! Now I can really see it!

G treats sky and earth not as nouns but almost like verbs.

It feels like everything’s moving!

That sudden sense of a still world springing to life—that’s how I felt after the Restoration of the Earth workshop, and I think I know why now.

In short, these practices let wind be wind and soil be soil—they set a still world in motion again.

And I believe architecture, too, becomes more alive when we think from within this worldview.

This also pushes forward the idea of “play” I mentioned before.

You draw things close through play, then release them back into the world as living dynamics, nudging the whole to move.

Taken together, I think this too is “play.”

Makes sense.

That first question—a harmonizing way of thinking—maybe starts with imagining a world full of activity.

The contradictions of modern civil engineering and the potential of “Restoration of the Earth” and “Subsurface Environment.”

It took time before I could really feel this, and—like animism—I felt the need to put it in my own words.

Once I framed these approaches as methods for setting a still world back into motion, it finally clicked; but the Cartesian worldview still dominates architectural thinking.

If we can update that worldview—those images—architecture may become far richer.

That’s what I’ve been thinking about lately.