Can you keep going?

First, a quick recap.

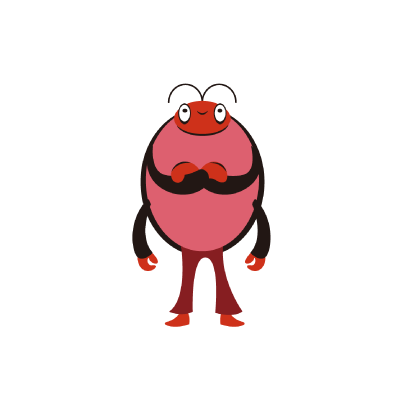

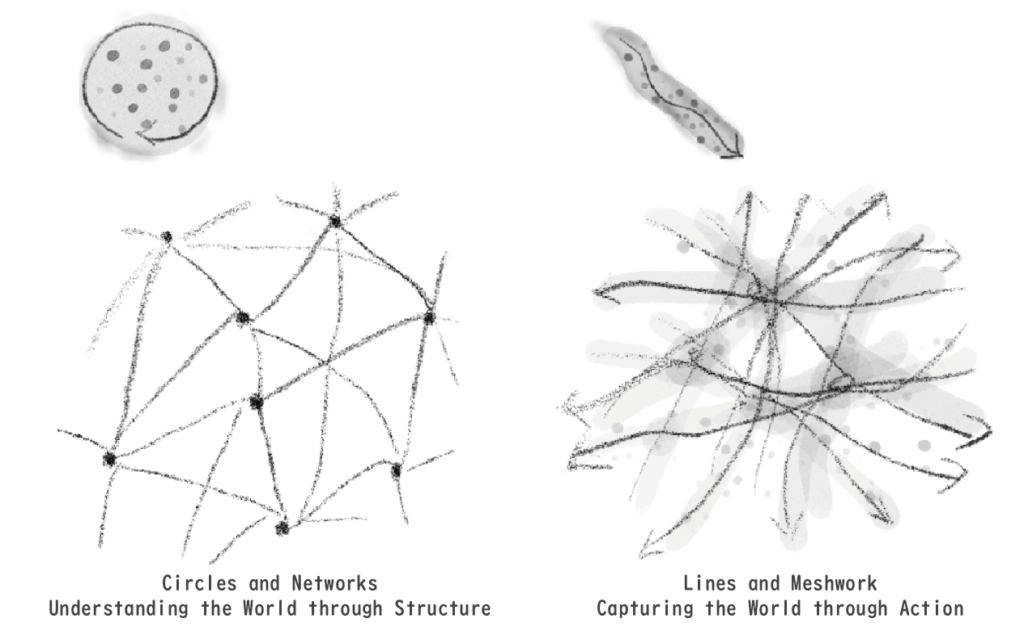

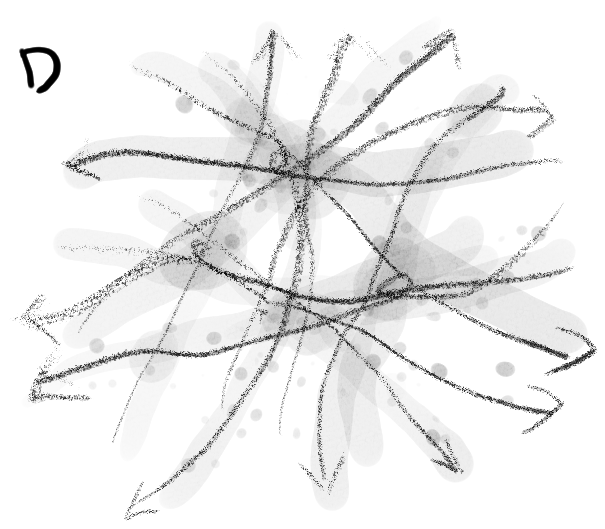

There are two ways of seeing life and the world: one with closed circles and networks, and one with open lines and meshworks.

A network views the world in terms of composition, while a meshwork views it in terms of activity—you could also call this the difference between structure and system.

Here, it’s crucial that the lines in a meshwork are open.

A closed circle looks self-contained and complete.

In other words, the circle appears separated from the world and objectified—just like Descartes’s move to divide the world up and objectify it.

By contrast, an open line focuses on activity, so it’s less separated from or objectified by the world than a circle is.

Since the world is the very state of many lines moving and intertwining, isolating a single line by itself doesn’t mean much.

So how does the meshwork worldview correspond to animism?

People living in an animistic world (animists) sometimes talk about weather—like wind and thunder—or inanimate things—like stones and water—as if they were alive.

Like the view that spirits dwell in all kinds of things.

Right.

From our standpoint, that often gets read as “people in so-called primitive societies don’t understand the difference between living and nonliving things.”

I’m not sure whether they truly don’t get it, but that does feed into the suspicious vibe people have about animism.

Given our worldview, treating inanimate things as if they were alive does feel odd.

But what if, for animists, there’s something far more important than distinguishing living from nonliving?

Something more important?

Yes.

Ingold says there are two common misunderstandings about animism.

First, what animism values is not a way of knowing the structure of the world, but a way of living in the world.

Second, rather than “inserting souls” into inanimate objects, animists first take every kind of being—regardless of the living/nonliving distinction—as part of this world.

Here’s the fundamental mismatch.

With a Cartesian worldview installed, we try to know the world’s structure and conclude that wind or stones aren’t alive.

But for animists, what matters is a way of living in the world, and whether wind or stones are classified as living isn’t all that important.

Let’s look again at the meshwork diagram.

Imagine that one of those lines is you.

To live means moving through this mesh of intertwined lines, forming relations with other lines as you go.

At that point, do those lines have to be limited to living things?

Last time, I wrote “a meshwork is a world woven from the activities of diverse living beings,” but in truth wind, earth, and every other kind of activity—regardless of the living/nonliving distinction—also form the meshwork.

Yeah, that makes sense.

When you think about what your life interacts with, it doesn’t matter whether it’s alive or not.

Exactly!

This meshwork image fits the animistic worldview that focuses on ways of living and on activity, and regards the world as such—whether things are living or not.

We’ve become obsessed, in a Cartesian way, with slicing up the world to know it.

For those of us who’ve forgotten what it feels like to live within the world (*1), amidst intertwined activities, I think the animism = meshwork worldview contains something essential.

And in fact, forgetting the animistic perspective has already caused various problems.

I still can’t quite picture it.

What kind of problems do you mean?

Could you explain a bit more?

I’d wanted to rephrase animism in my own words, and when I overlaid animism with the meshwork idea, something clicked into place.

Animism is a way of living—that is, a way of seeing the world from the standpoint of the living subject—and it centers attention on activity.

Once I thought of it that way, it linked all at once with ideas I’ve been exploring, like affordances and autopoiesis.

Going into those links would make this too long, so I’ll just touch on them here—but I have a hunch this view lets us grasp the world more richly.