So… you were saying modern thinking has reached its limits. What do you mean by that?

It’s not as complicated as it sounds.

Modern humans—Homo sapiens—are said to have appeared around 250,000 to 400,000 years ago.

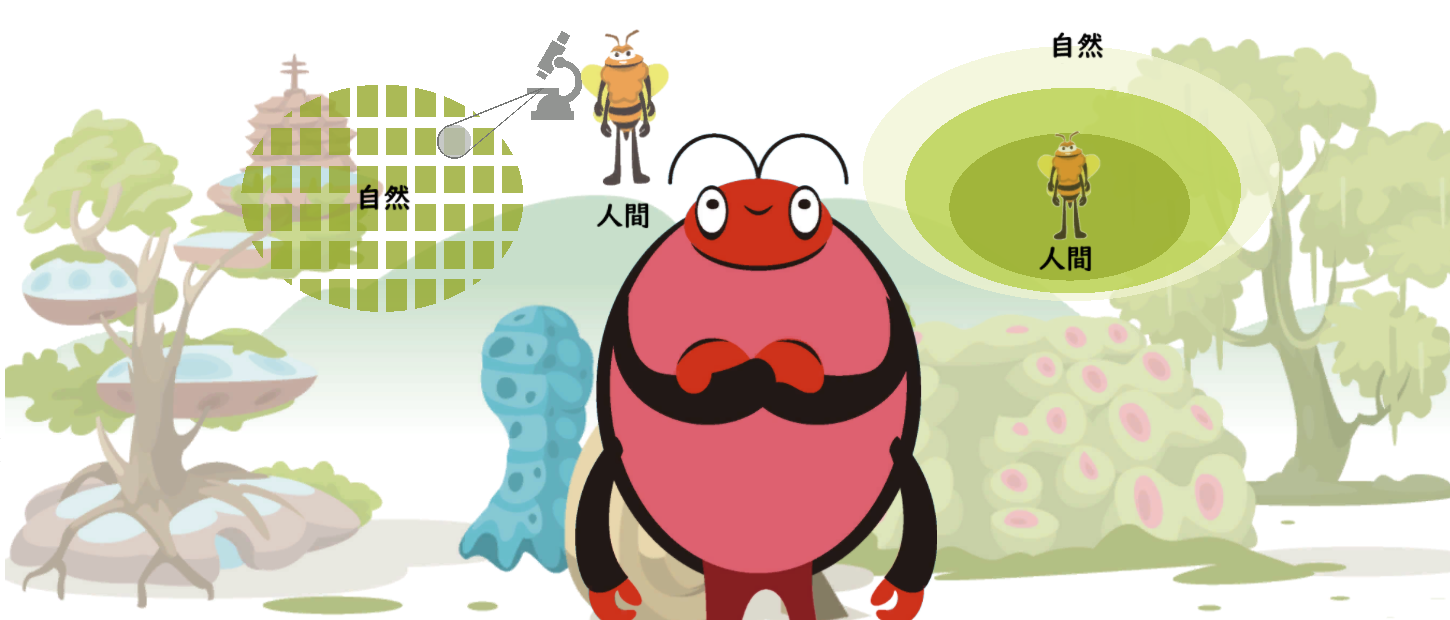

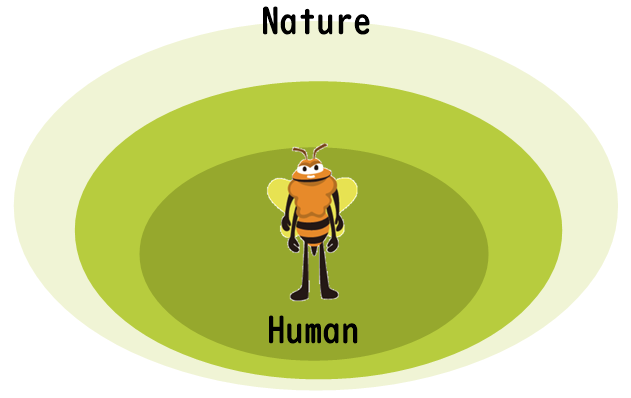

For most of that long history, people saw themselves as just one part of nature.

Living in harmony with nature was essential for survival, so they accumulated wisdom to maintain that balance.

Yeah… I can kinda see that.

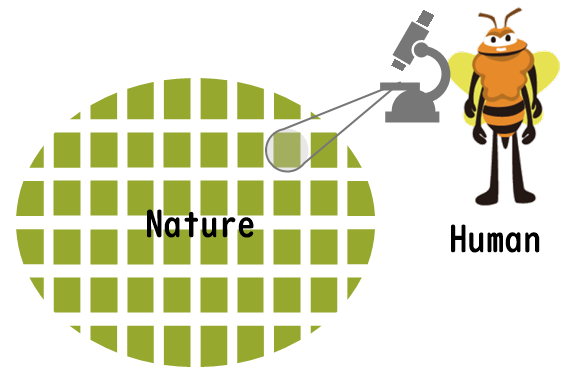

But then came the 17th century. Civilization advanced, and a philosopher named Descartes basically said, ‘Humans and nature are separate things.’ (*1)

That idea made it easier to study nature. Whether Descartes actually believed it or was protecting himself from the Church is hard to say—after all, the Church was powerful back then.

He also argued, ‘Let’s break nature into small parts, analyze them, and by understanding each part, we’ll understand the whole.’ (*2)

This way of breaking the whole into pieces became the foundation of modern science. And modern science gave us the world we have today.

So Descartes was a genius, huh?

Absolutely. We owe much of modern wealth to him.

But at the same time, we lost the wisdom of seeing the whole picture. People became blind, focusing only on what’s visible—on the pieces—forgetting the harmony of the whole.

Hmm… so what’s the problem?

Not knowing what the problem is—that’s the real problem.

When you focus only on parts, you lose sight of the whole. If something looks fine right in front of you, you assume everything is fine.

Separating humans from nature—or yourself from the rest of the world—leaves you with a perspective limited to ‘here,’ ‘now,’ and ‘me.’ (*3)

That’s the core of the environmental crisis.

So in the last episode, we talked about The Ideology of Division and Shifting Burdens.

You’re saying the division part blinds us.

So what about shifting burdens?

‘Shifting burdens’ means passing the responsibility elsewhere.

Environmental problems get hidden away through technological shifting, spatial shifting, and temporal shifting—so they disappear from view as if they don’t exist.

Could you give an example?

Take technological shifting:

We invent a new technology, thinking we’ve solved a problem.

But usually, that technology creates a different problem somewhere else—a problem we don’t see.

For example, new ecological tech requires rare metals. Mining them consumes massive energy, destroys ecosystems, and exploits vulnerable communities.

But we don’t see it—it happens far away. (*4)

That’s spatial shifting:

Our wealth here depends on poverty or destruction somewhere else.

And temporal shifting:

Today’s comfort comes at the cost of the future. We barely think about the people who’ll live decades from now.

I get it now.

Division blinds us, so we don’t even realize we’re shifting burdens elsewhere.

And problems you don’t see… you never solve.

Exactly.

We have endless information today, but because the mindset of division is so deeply rooted, problems feel like ‘someone else’s problem’ far away.

And that’s terrifying—because it makes the problem almost nonexistent in our minds.

That’s why I say: Unless we recognize the flaws in modern thinking itself, we can’t truly solve environmental problems.

We need both Descartes’ analytical thinking and the ancient wisdom of harmony.

Only then can we talk about technology, energy efficiency, and architecture.

Semuu…

…Seems like Semuu wants to hear about architecture already. Let’s move on to that next time!

Modern thought has a structure that makes problems vanish—at least in our minds.

Recognizing this is the first step toward addressing environmental issues.

But humans can’t easily escape this way of thinking.

The real challenge—and the hope I see in architecture—is whether we can turn environmental action into something natural and enjoyable, rather than a burden or obligation.