Come to think of it, Onon.

That “ingenuity originally built into architecture” you mentioned before — what did you mean by that?

Ah, that refers to the fact that before electricity existed, buildings inevitably incorporated various ideas to make use of the energy naturally available around them.

It seems obvious, but over time, even architects have forgotten about this obvious ingenuity. (*1)

Also, buildings used to be adapted to the local environment, which gave them a sense of place and regional character.

The loss of that regional identity is a big loss indeed.

Yeah, maybe the sense of local character really has faded.

But back to the topic of ingenuity — in Japan, what kind of ideas did they use?

Traditional folk houses and Kyoto townhouses are well-known examples.

As Yoshida Kenkō once said, “A house should be built with summer in mind,” so many of these design ideas focused heavily on summer.

After all, in winter you could stay warm by burning something, but to stay cool in summer, without electricity, you had to get creative.

Yeah, that makes sense.

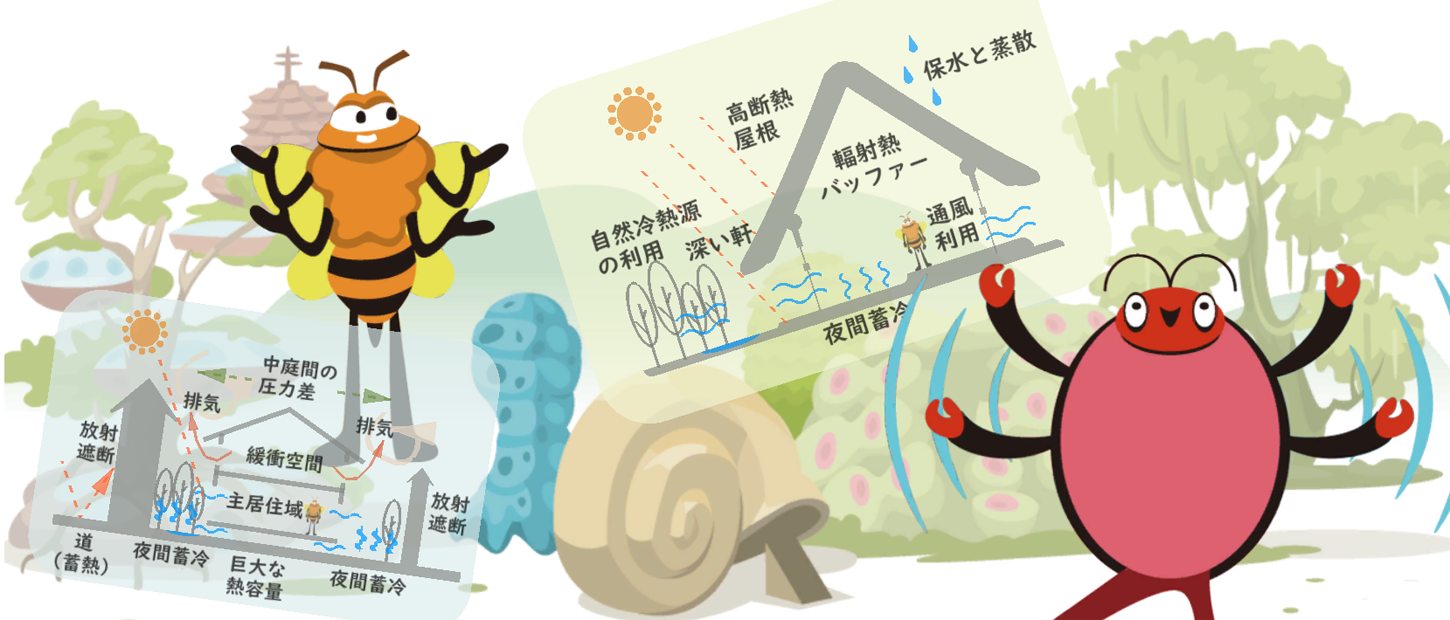

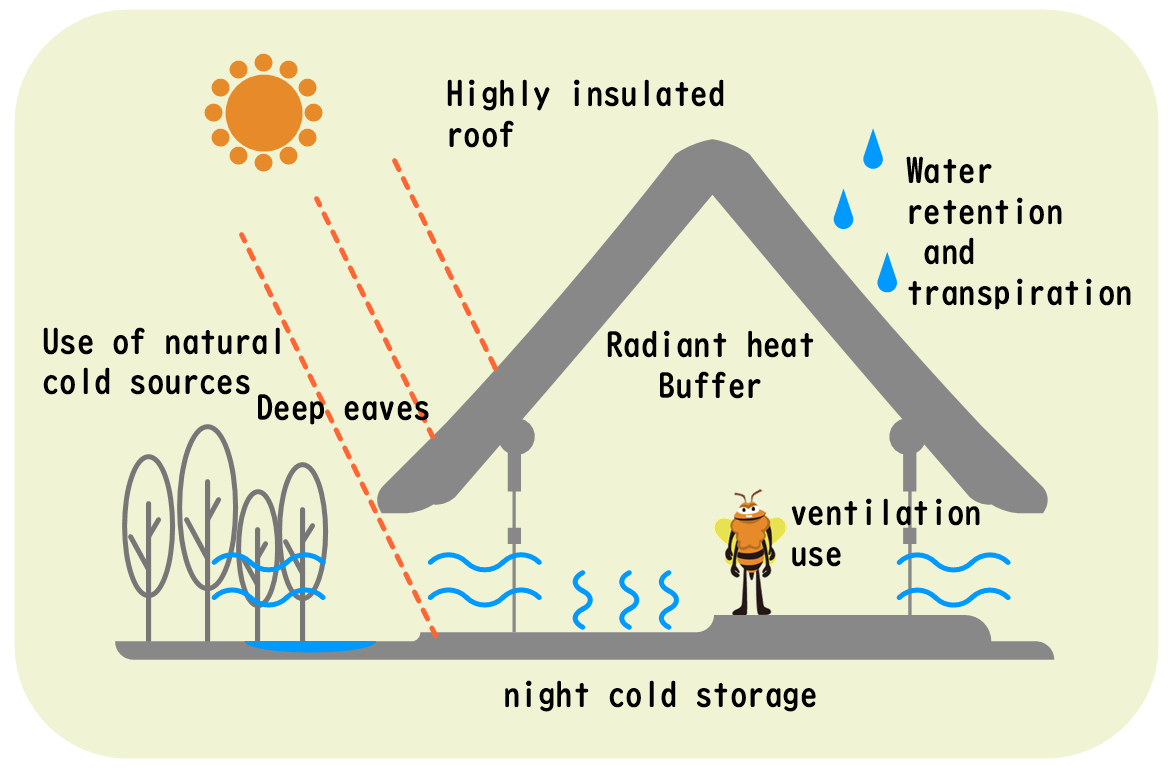

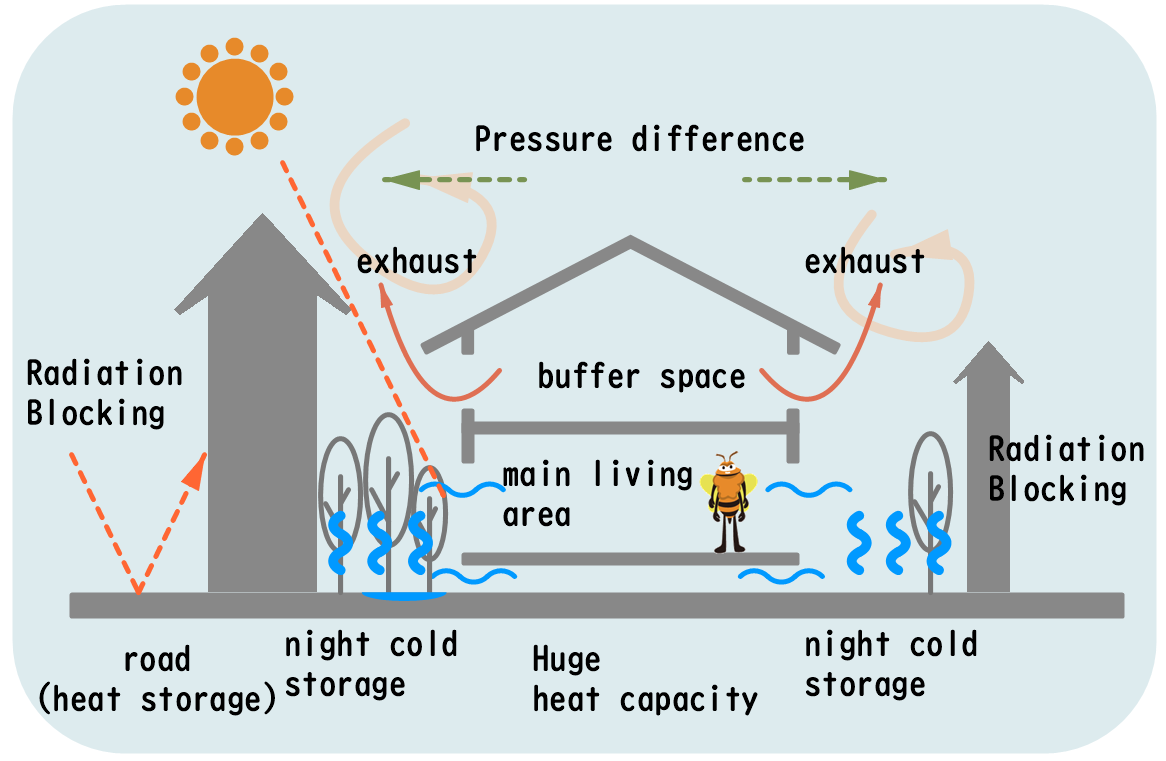

For example, traditional folk houses had super-insulating, water-retentive thatched roofs that blocked out solar heat while providing evaporative cooling.

They also had highly open sliding doors and paper screens that allowed breezes to flow through, while gardens and ponds cooled the incoming air.

Moreover, earthen floors stored the night’s radiatively cooled air, acting as natural thermal masses.

Each material and its placement had environmental meaning behind it.

Sounds like summers there must’ve been really comfortable.

Cool and pleasant indeed. Kyoto townhouses were even more fascinating.

Being in urban areas, they couldn’t rely much on cool breezes from outside, so the concept was completely different from rural houses.

Townhouses had multiple inner courtyards. The deeper ones, receiving little sunlight, served as cold-air reservoirs.

At night, the open courtyards cooled significantly through radiative cooling.

At the same time, these courtyards also acted as ventilation shafts to release heat and pollutants from inside.

Wow.

Actually, having multiple courtyards was the key.

Because each courtyard had slightly different environments and wind effects, air pressure differences developed, causing gentle breezes to flow through the interior.

You could even adjust this with sprinkling water — truly a passive environmental cooling device.

Unfortunately, since people today don’t fully understand this concept, some have blocked off these courtyards, reducing the cooling effect.

That’s super interesting.

But I wonder… doesn’t that mean the houses were freezing in winter?

I often hear people say, “Old houses were poorly insulated, so they need retrofitting” — were they not eco-friendly after all?

I wouldn’t say old houses weren’t eco-friendly.

The environment back then was completely different.

Sure, winters must have been cold, and they probably burned a lot of firewood for warmth.

But population density was much lower, and the firewood they used came from the natural cycles within their own region, so I don’t think the environmental impact was that large.

It’s more that as the environment changed, this way of living no longer matched the idea of controlling the climate with external energy sources like electricity.

I see.

Hmm… So did these old ideas die out because they became useless?

I’m not so sure.

Many things stopped working well as the environment changed, but I believe these ideas can still be used today — as long as we adapt them to modern conditions.

More than that, I think these traditional ways of building hold important hints for enriching architecture.

In fact, I believe these houses provided a sense of reality — that we are living in this world.

That’s why I want to call architecture with such qualities “21st Century Folk Houses.”

Sounds like this is about to turn philosophical again.

Well… I’ll do my best to keep up!

It’s fascinating to study the ingenuity of traditional houses.

It feels like such a waste that these ideas haven’t been passed down. I think this also reflects the influence of modern thought frameworks.

Adding these kinds of design ideas requires people willing to engage with them — and that comes with a bit of effort.

Whether someone sees that effort as a burden or as fun depends on the person, but perhaps our modern world doesn’t leave enough room for such engagement.

In reality, once you start working on something, the fun often outweighs the hassle, but there’s a psychological hurdle — you don’t discover the fun if you never start. (This is what psychology calls “work excitement.”)

This leads into the topic of reality, which I’ve been thinking about even before my focus on environmental design — but that will be for next time.