By the way, Onon.

I still can’t quite picture what you meant by the philosophy of harmony you mentioned at the very beginning.

I get that the philosophy of division is a problem, though.

Back then, I didn’t have a clear picture myself, so that might be why.

Since then, I think I’ve understood it a bit better, so let me try to explain.

I think I mentioned that before the Cartesian “philosophy of division and transfer,” the philosophy of harmony was dominant.

That was actually inspired by the philosophy of animism (*1).

Animism?

Sounds a bit suspicious to me.

Animism is often translated as spirit worship, and yes, it does have a spiritual vibe, and maybe even the strong image of a primitive and inferior way of thinking.

But I think this idea holds hints for overcoming the philosophy of division and transfer.

So I want to try stripping away the suspicious image of animism.

Hmm, as usual, I can’t really picture it, but okay.

This might be a bit roundabout, but to do that, I want to start by replacing the image of life using the concept of lines and meshworks proposed by the anthropologist Tim Ingold (*2).

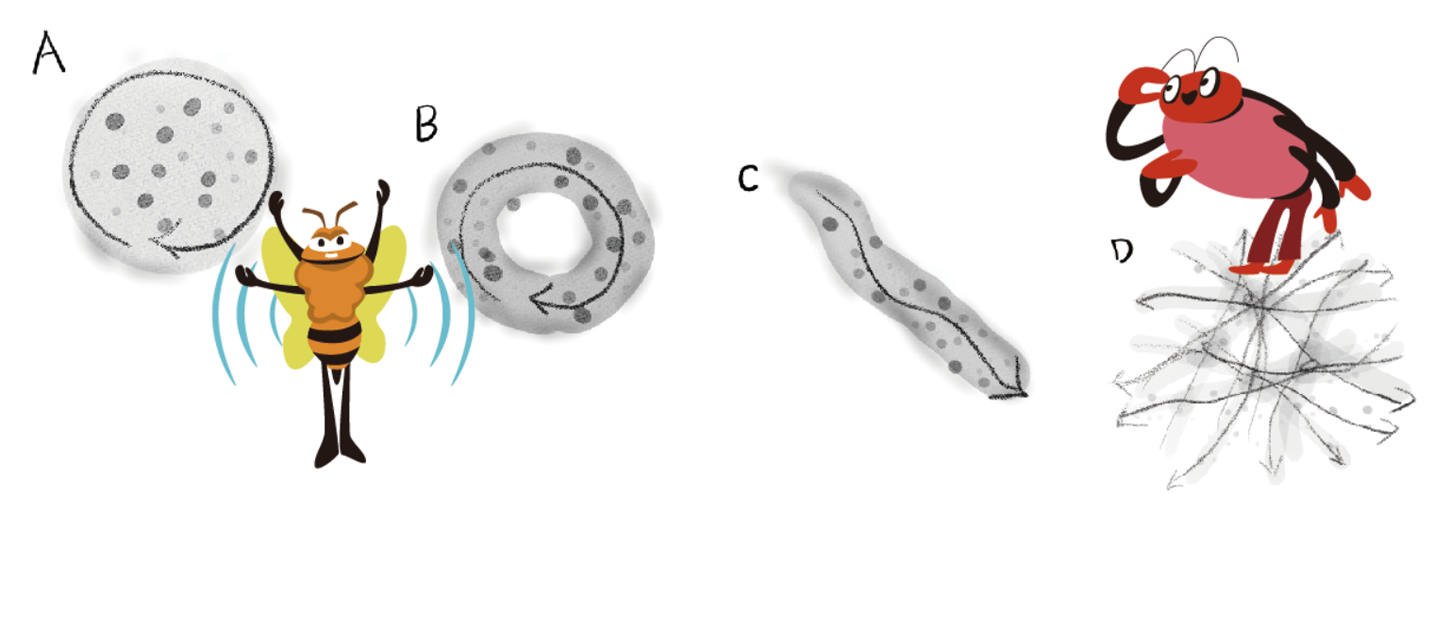

Earlier, I described life systems as “systems that keep cycling endlessly, creating boundaries between self and non-self through their very workings”.

Let’s call that Image A.

It’s the idea that boundaries arise from the self-driving system itself.

But actually, many organisms live inside our bodies, and various foreign elements pass through as well.

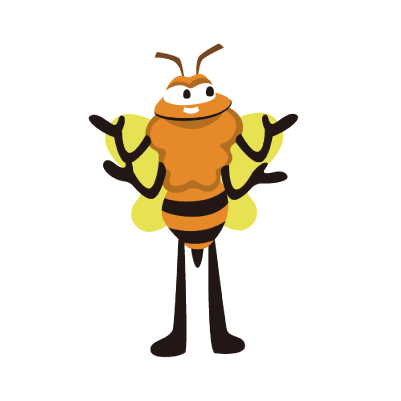

So, to weaken the A-image of “inside vs. outside,” I imagined a swirling activity around which various elements intertwine, forming temporary unities (B).

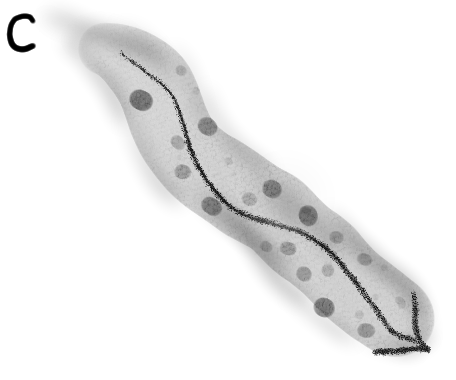

I think B is a pretty good image, but here Ingold thinks of life not as a circle but as a line.

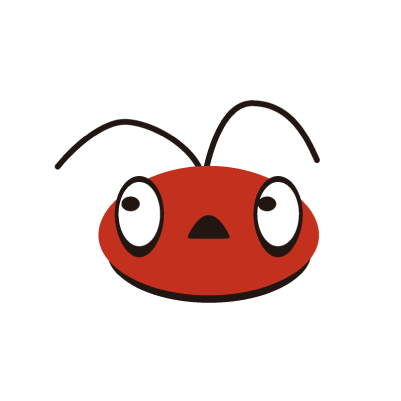

If we unravel B’s circle into a line, we get C.

The image of various elements intertwining around activities to form temporary unities becomes even clearer.

What does it mean for circles to become lines?

I mean, C feels kind of lonely somehow.

It feels lonely because you’re looking at it alone.

What’s the difference between circles and lines?

Here lies a hint for overcoming the philosophy of division and transfer.

Circles look like a single closed lump. I’ll explain later, but this way of seeing suits the worldview that divides everything. It’s also about seeing life as an object (*3).

On the other hand, lines are open, expressing life more as activity itself rather than as a lump.

In other words, circles vs. lines show the difference between viewing the world as structure (how the world is constructed) or as system (what activities the world consists of).

This difference in worldview changes how we see life.

Structure and system, huh?

Hmm, not sure I get it.

For now, just remember: circles are lumps, lines are activities.

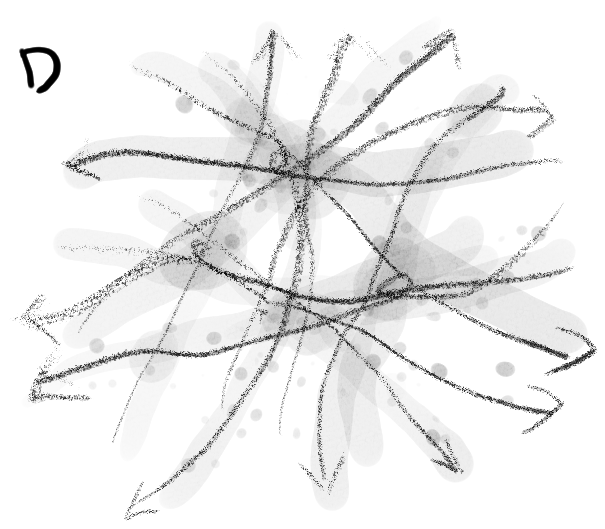

Here Ingold tries to replace the world’s image from networks to meshworks.

Earlier, you said life in C looked lonely, but life as lines doesn’t stay inside a circle—it ventures out into the world, intertwining with many other lines.

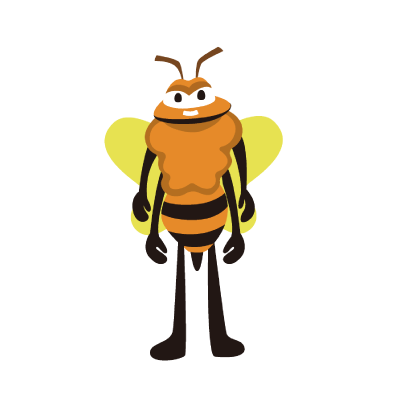

From microbes to humans, the world full of intertwined activities of diverse organisms is what he calls a meshwork, and far from lonely, it’s a vibrant and dynamic world (D).

Meanwhile, the worldview that divides the world into small circles often imagines a network of lumps placed in the world and connected by relationships (E).

Doesn’t this network worldview seem less dynamic compared to the meshwork worldview?

Even though relationships between nodes in a network should also be constantly shifting, once life is reduced to a point, it inevitably feels static.

In this way, whether you see life as a closed circle or as an open line leads to whether you see the world as a network or as a meshwork.

So it’s like stillness vs. movement.

I kinda feel like lines do have more dynamism, but what does that have to do with animism?

Of course.

These two perspectives are connected to the difference between the Cartesian philosophy of division and transfer and the animistic philosophy of harmony—but I’ll explain that next time.

Episodes 2–3 referenced the contrast between Cartesian dualism and animism described in The World After Capitalism.

But I felt that the term “animism” had too strong a spiritual connotation to use as-is.

Animism has been widely debated in cultural anthropology, and when I was wondering how to reframe it in my own words, I came across Tim Ingold’s Being Alive.

What I thought about while reading it will be written across three parts: the first, middle, and final.