Niki, we finally finished harvesting the rice. If you’d like, please have some.

Thanks! With rice prices going up, this really helps! Wasn’t rice farming pretty tough?

It was, and I made plenty of mistakes.

But honestly my takeaway is: it isn’t as grueling as people say—once you try, you can manage.

And there’s a lot you only understand by experiencing it.

Like what?

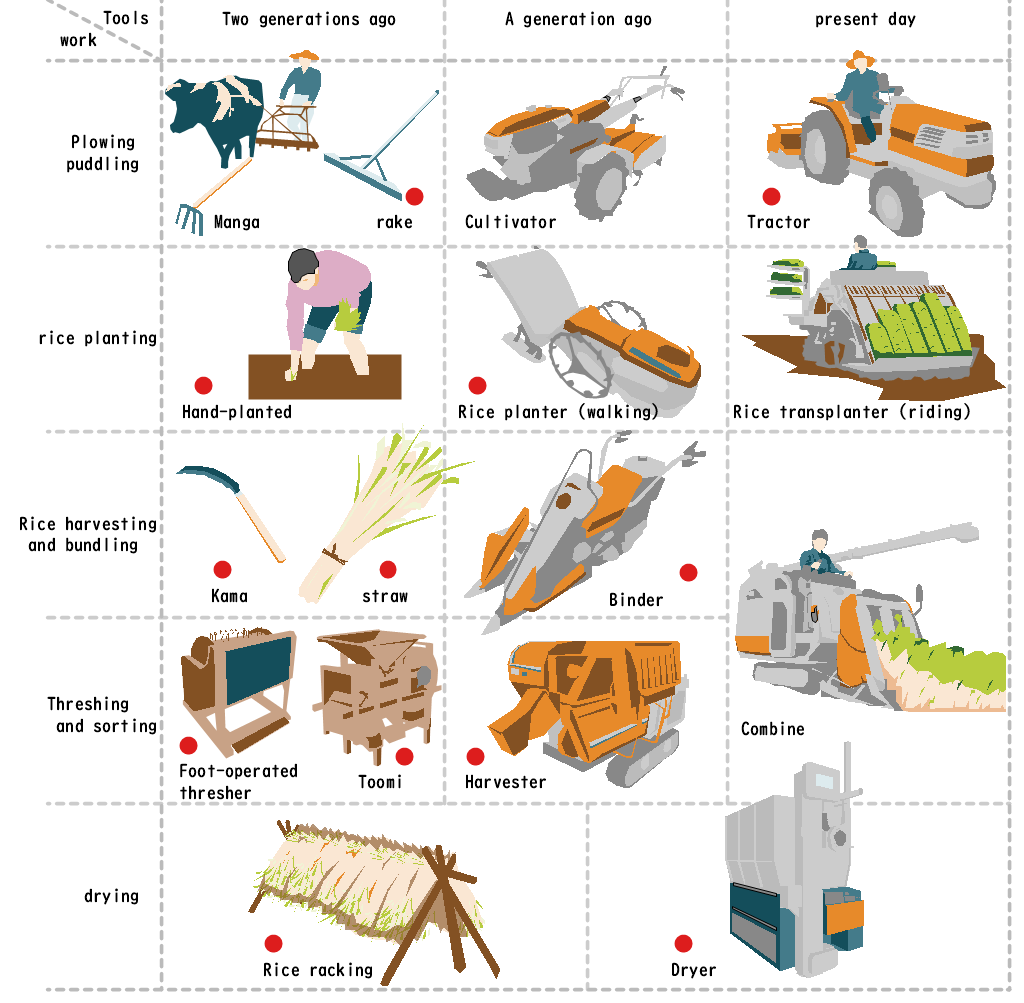

Generations of Tools and Their Value

For example, rice farming uses many tools, and I learned that each “generation” of tool carries different values and meanings.

The generations look roughly like this.

Wow, there’s a lot!

The tools on the right are mainstream today. In practice, the middle and right are mixed.

The red circles mark what I used this year, and I tried to do as much as possible with the older tools on the left.

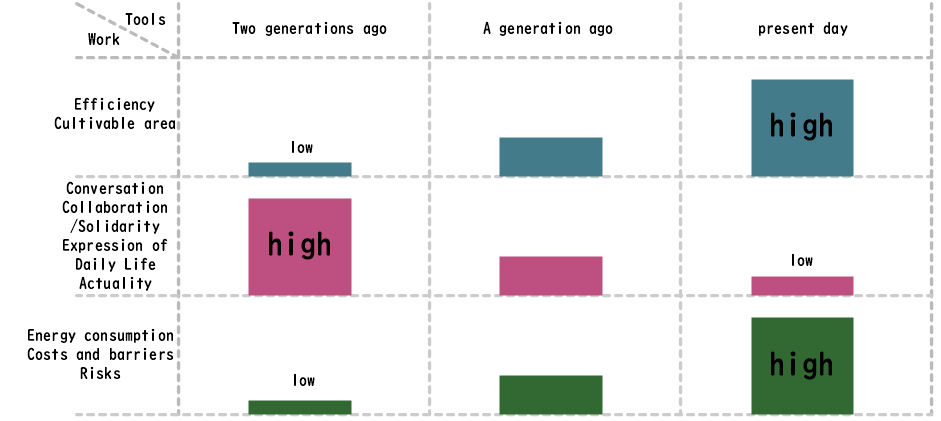

Here’s what I realized about their value.

In short, the farther right you go, the more efficient the tools become and the larger an area you can handle.

But in exchange, energy use and costs rise—creating a barrier to entry. Tasks get riskier, and because you work alone, it turns into solitary, purely “mechanical work.”

So you used the left-side tools mainly to keep costs down?

That’s part of it.

We couldn’t reasonably till and puddle by hand this time, so I asked a neighbor to do it with a tractor, and that fee alone was around 40% of the total cost.

Left-side tools are cheap—or donated—so costs are minimal, but your workable area is limited.

If you bring in machines to cover more area, costs inevitably become an issue.

I’m certain the upscaling of machinery is the single biggest barrier to small-scale rice growing.

My goal wasn’t to make money; it was the experience itself and maintaining the landscape.

So I aimed to use tools on the left.

What I found is what you see in the middle row of the chart: “conversation, collaboration/solidarity, the expression of daily life, and actuality” all rate far higher with left-side tools.

Once you shift to powered tools in the middle and right, conversation and solidarity suddenly vanish—that was striking.

So next year you’ll stick to the left-side tools?

I’m still torn.

From experience, if one family plus a few friends help out on weekends, the workable area is roughly:

・Left side: up to 1 tan (≈ 1,000 m²)

・Middle: 1–3 tan

・Right: 3–10 tan

This year I had 1.5 tan, so just left-side tools were tough; in the end I relied on a neighbor and used a mix from the middle and left.

So next year I’m debating: keep 1.5 tan with mixed tools, or do half that area using as many left-side tools as possible.

But if I cut it in half, the harvest would be about enough—or maybe not quite—for my family for one year (*1).

If I want to offset cash outlays and share some with those who helped us, 1.5 tan is ideal.

I see—tricky decision.

Efficiency-wise, about 1.5 tan with middle-generation tools is probably the sweet spot.

But if I return to my original aim—“the experience itself and maintaining the landscape”—then the values embedded in the left-side tools matter most.

I’d love to see more people casually try rice growing on weekends, and for that, the left-side values are crucial. Getting the scale–tool balance right feels very important.

In that chart you mentioned “conversation, collaboration/solidarity, expression of daily life, and actuality.” I can imagine the first two, but what do “expression of daily life” and “actuality” mean?

Tools and Landscape

They’re related, but let me start with the expression of daily life.

By that I mean: your lived daily activities appear openly, in public view—the kind of landscape that emerges.

Earlier I said powered tools reduce tasks to pure “work.” People rarely smile when they’re just grinding through tasks.

Doing something is better than doing nothing, of course, but watching a landscape of purely mechanical labor isn’t exactly uplifting.

With left-side tools, many hands work together, so conversation and smiles naturally arise.

And because the work is less hazardous, kids can join in.

(I wish I’d taken better photos…)

Also, nowadays people often harvest with a combine and dry the grain in a machine, but the scene of sun-drying on racks (hazakake) is still wonderful.

The rice tastes better, and you get straw as a byproduct. In the past, straw craft was woven into everyday life.

It really does look fun!

Enriching the landscapes we live in is vital—and it connects deeply to architecture.

Realizing how much tool choices shape the expression of daily life and the landscape might have been my biggest discovery.

Right now, we default to efficient tools because economy gets prioritized as the only value.

But shift the point of view and other values appear. I think that will be crucial going forward.

Makes sense!

So, what does “actuality” mean?

It ties closely to architecture too—but this is getting long. Let’s pick it up next time.

For the background of this project, see [Tag: Insect Rice].

As I wrote above, perhaps the biggest lesson from trying rice growing is that tool choice matters far more than I expected.

Usually, we pick the most efficient tool for the situation—that’s the conventional logic when economy is the only value.

But if you look instead at values like enriching the local landscape, enjoying the experience, or building the capacity to live, your choices widen.

That connects to teaching children how to live by different stories, and ultimately to grasping the felt reality of “we are living in this world.” I’ll try writing about that next time.